I’ve been watching Riverdale (a fact which has prompted a little self-analysis of what exactly I like in a movie or TV show, but that is neither here nor there), and a recent episode did something that I’m sure there should be a term for.

(Spoilers follow. Oh yes.)

Riverdale, for those of you who don’t watch it, is a pulpy neo-noir crime soap teen drama thriller with a faintly retro feel. It’s clearly fond of classic movies (every episode is named after one, usually crime or thriller but sometimes horror). It’s not quite real in a couple of subtle ways. All the main characters are juniors, but they’re also seventeen years old, for example.

One of the patterns (not hard rules) is that leaving Riverdale doesn’t quite work. In the show, three people have done so. One is Jason Blossom: he died. One is “Mrs Grundy”; she made it to Greendale, but was murdered. One was Joaquin, who left by going on a bus to San Junipero – that’s the eponymous town from an episode of Black Mirror which is actually a fictional world where people’s consciousnesses are uploaded after death. (Before the show began, there was also Archie’s mother, and Hermione Lodge – in the context of the show, they both start outside Riverdale and come back to it.) Archie’s mother gets to leave again, but overall, the pattern you see again and again is that people don’t leave Riverdale, and if they do they die.

So. The episode I’m thinking of was called “Tales from the Darkside” and told three short related stories.

In the first, Jughead owes someone a favour, so he needs to deliver a crate to Greendale. He doesn’t have a car, so he asks Archie to drive his, and while they’re en route a tire blows out. A truck driver comes by; he says he’s going to Greendale, he’s got room for one of them and the crate if they pay him, and Jughead agrees to give him all his money ($18) in exchange for the ride.

The first thing the driver says, once they’re moving, is that for a minute he thought Jughead’s friend was Jason Blossom. The driver (played by Tony Todd) then starts telling Jughead about the Riverdale Reaper, a mass murderer from fifty years ago. They stop for gas, and Jughead discovers that the guy has a dead deer in the back of his truck.

Meanwhile, Archie calls a repair service, gets his tire replaced, and drives on. He reaches the point where the sign on the road says

<- RIVERDALE

GREENDALE ->

and stops for a second. A deer crosses the path, strolls straight across the road, and disappears into the woods behind the sign.

And, alright, practically speaking, it’s not that anyone actually can’t leave. Archie catches up with Jughead and they make the delivery.

But in terms of subtext…

- Jughead gets a ride from someone.

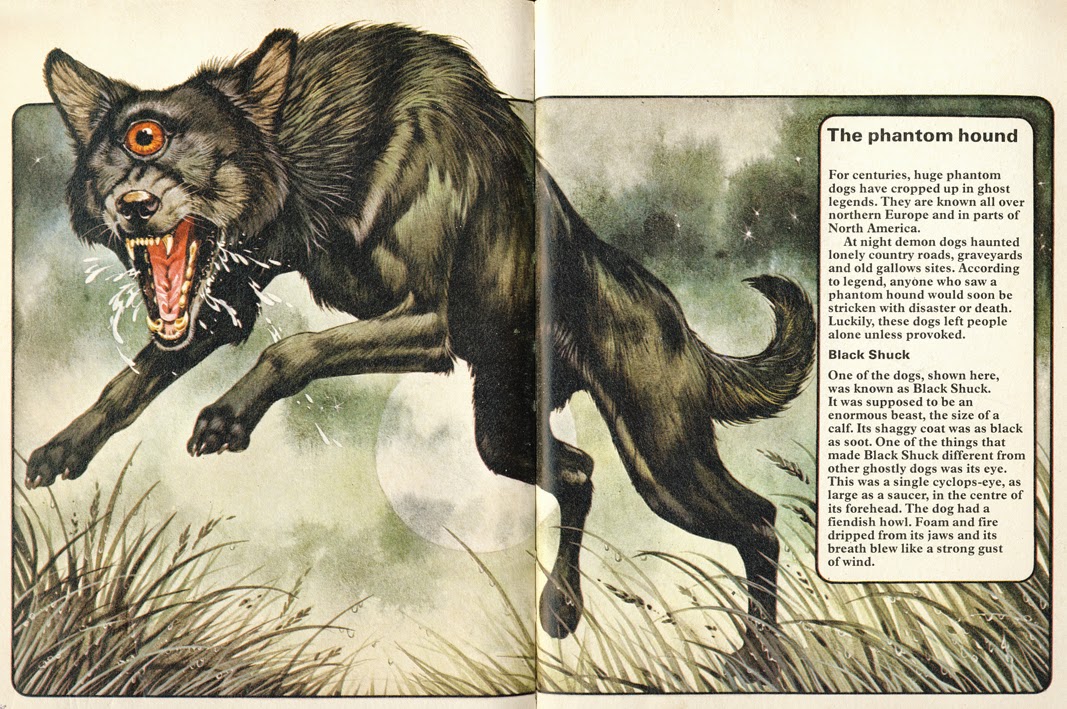

- This person, in a show that loves and references movies, and which is specifically referencing horror movies with this episode, is played by the actor who played the urban legend/killer/living story from Candyman, and who was Death in the Final Destination series.

- The first person the driver indicates he knew is a boy whose defining characteristic throughout the show has been that he’s dead. It drives the entire first season.

- The first name the driver brings up (and he never brings up his own) is that of the Reaper.

- This man demands all of Jughead’s money in exchange for ferrying him across the border.

- We see a living deer as the creature that walks along the border between Riverdale and elsewhere.

- We see that this man has a slaughtered deer in his truck; literally, the thing that marks the border, destroyed and made powerless.

This is absolutely the story of Jughead being stuck delivering a questionable substance to repay a favour. You know he’s not going to come to a Tales from the Crypt terrible ending. He’s got to stick around. We know this.

But it is also the story of someone being taken across a border by a stranger who is all but wearing a T-shirt saying “Ask me about my role as the Grim Reaper, Guardian of the Threshold and Ominous Bringer of the End.” And we know that as well, and we can enjoy the beats of that story even as we are sure they will never happen. And the beats of that story both exist and shape our expectations of what will actually happen.

There’s a word for this, isn’t there? Telling one story, but telling it in the shape of another?