Foz Meadows (Shattersnipe: Malcontent & Rainbows) has something to say about TV romances, conventions, expectations, and shortfalls.

Category: Stories, Packaged and Sold

Category covering assorted forms of narrative media; books, comics, movies, TV shows, and video games.

I think TV Tropes has a name for this

I’ve been watching Minority Report, and while I wouldn’t call myself a fan[1], there was a kind of striking moment in the seventh episode.

To summarize the basic premise, established in the pilot: Dash (one of the precogs) is the hopeful nice one who’s voluntarily (and secretly) assisting the police, and his brother Arthur is your basic languid-sleaze-in-a-suit using his powers to steal people’s identities and generally make headway as a white-collar criminal. Lieutenant Vega is the police officer who knows what Dash is and is working with him. (There are other characters who are not relevant to what I am discussing.) Spoilers follow. Continue reading “I think TV Tropes has a name for this”

Romance! (No, really. Wait.)

I was discussing Leverage with someone–one of my favourite TV shows–and they described it as a bad but fun. And I asked why it was bad, and they described several qualities of it, and one of them was “it makes no attempt to be realistic.”

And something clicked for me. I’m going to turn to an English-as-a-subject ramble here for a moment.

Do you know how you can make a strong argument that Frankenstein isn’t a novel? That The Hobbit and The Mists of Avalon and The Phantom Tollbooth aren’t novels?

Because a novel is also a genre definition and that definition is “a book-length work of realistic prose fiction”.[1] The books I have mentioned are not novels; they are romances, where the definition of a romance is “a prose narrative treating imaginary characters involved in events remote in time or place and usually heroic, adventurous, or mysterious”.

(This is why the H.G. Wells Historical Society talks about his scientific romances, which is a term which was also applied to A Princess of Mars. We’re talking romance as a thing that gives us giant submarines and time machines and alien princesses, here.)

Getting back to Leverage: no, it is not remote in time or place. (It is in a TV-land where people are surprisingly pretty and such things as ledger deposit slots exist, plus there’s what Hardison does anytime he’s near a computer, plus Elliot… Alright. It is not blatantly remote in time or place, although it’s pretty clearly not next door.)

But it is certainly heroic and adventurous. It is a pulpy show, in the best sense–Lester Dent’s essay on pulp fiction writing is absolutely not posted on the wall of the writer’s room. 😉

No-one has to like fiction that isn’t realistic, and you can definitely make an argument for defining fiction that isn’t realistic as being silly. (I personally would be inclined to disagree, but I can see the pattern and structure of the argument.) But I think that to define a work of art as a bad example of the art, it’s important to engage with it in terms of what it’s trying to be.

Possibly more thoughts later.

=====

[1] Specific definition plucked from Dr. Doyle’s SF Genre Rant.[2]

[2] Now that you’ve read that essay, please note that I’m not arguing that genre fiction cannot be realistic in both senses described in it, but I think the realistic vs. romantic distinction is useful for the point I am trying to make about the TV show I was discussing, which I will now get back to.

Incluing at one remove

I’ve realized there’s a specific kind of world-building I’m interested in, and I’d love examples of it, if anyone has them: the kind in which the reader learns a truth about the world that is not apparent to the narrator/protagonist/viewpoint character(s).

Examples, off the top of my head

- “Petey” – TED Klein – probably the most full-fledged example of the lot, for reasons described below. None of the people attending the house-warming party know what’s going on. The attendant taking care of the former house owner doesn’t know what’s going on. None of them ever realizes during the text. But the reader understands.

- “The Events at Poroth Farm” – TED Klein (I sense a theme)

- “Fat Face” – Michael Shea

- “The Essayist in the Wilderness” – William Browning Spencer – the narrator assumes he’s observing the behaviour of crayfish. Those are not crayfish.

- The Steerswoman series – Rosemary Kirstein

(The latter four are probably easier to pull off, in that the protagonists discover the facts they are ignorant of before the end of the story, but at a point where the reader already knows. “Petey”, on the other hand, does not do this and remains a story that in this regard is so beautifully executed I am in awe every time I read it. This makes it really difficult to dissect and analyze.)

It’s interesting that, with the Steerswoman exception, these are all relatively short works; two short stories, and two novellas. I imagine this might be the kind of thing that’s fairly hard to do without the reader growing exasperated that the characters haven’t figured it out.

Important Clarifications

Multiple viewpoint stories don’t inherently count. For example, in The Diamond Age, the reader knows more about the world than Nell and Hackworth and Judge Fang know individually, but what they know are factual details which are plausible within the presumed reality of the setting. The reader does not come away knowing that the world is reset-to-new-default-every-night-at-midnight in the manner of Dark City; that kind of thing would be a greater and occulted truth about the nature of the world, and not a default assumption within a future-set nanotech-driven earth. What I’m looking for is not merely a case of factual details being revealed, but of larger and different truths about the nature of the world being revealed.

The truth of the fictional narrative is not the default reality presented in the narrative. “Fat Face”, for example, presents a modern street-level existence; shoggoths are not assumed to be part of that default reality. The Steerswoman series presents a quasi-medieval-fantasy world which contains magic and which is just beginning to develop technology; the actual truth of the world contains things which are not assumed to be part of that default reality. But in reading each story, the reader learns a thing that they would not assume to be true based on the premise of the world.

Stories in which the narrator perceives A Secret don’t count. For example, say they’re running around seeing ordinary people as demonic creatures/animal-headed being which reflect their true nature/aliens only spottable with special sunglasses. If the narrator is right, then the reader doesn’t learn more about the world than the narrator. If the narrator is wrong, then the reader learns that the narrator is unreliable, and nothing special is revealed about the world.

(Technically you might be dealing with an unreliable narrator, but in a way which can also be reasonably described as them being an ignorant narrator.)

Finally, I’m looking for text only. This means that things like the I Am Legend movie do not count. It is a wonderful example of how what the viewer can see is really going on (as displayed on film) does not match what the protagonist asserts is going on, but I really want to see how this is made to work in text.

With all that said…

Suggestions? I’d love to read more of these.

Counting ink, 2015.

Now is the time for minutae-minded individuals to get bogged down in idly typing up details, so I’m posting about my reading and writing this year.

Reading

In 2015, I aimed for 70 books and finished 82, covering a total of 22535 pages.

Four of the books I read I five-starred on Goodreads, which is a rating I reserve for books that I think people should read even if they usually pass over that genre (A Gift Upon the Shore, “Sugar“, After the End, and Feeling Very Strange). The first is a novel, the second is a standalone short story (although it’s set in the Tabat universe, which also contains the really really lovely “Events at Fort Plentitude“), and the other two are anthologies.

Two of the books I read I two-starred, which means I did not hate them but pretty much stopped enjoying them and ground on to see if they would get better. If they had, I would have rated them higher.

And the oldest book I read this year was Fritz Leiber’s Gather, Darkness!, first published in 1943.

Writing

I submitted stories 56 times in 2015. I also got 49 rejections (one shy of a deciBrad, which I have decided is the correct term for ten centiBrads!), but three were from stories submitted before 2015, so you can say I only got 46 2015 rejections. (In 2014, those numbers were 34 submissions, and 31/30 rejections.)

I also got four acceptances, which was four more than last year. Or ever. Three of them have already been published; they’re linked over here.

This means I’ve got six stories out at the moment. I’m hoping to manage seventy submissions next year; will see how it goes.

Happy New Year! See you on the other side.

Come and get some mercy.

Well, season 2 of Z Nation is complete and I am giddy.

There are other shows with zombies (I am pretty sure… although these days I’m only watching iZombie, and it kind of doesn’t count). There are other shows with pulpy, bright-and-quickly-drawn characters. There are other shows with kind of cheesy premises that carry themselves through sheer momentum.

But.

A shining example to humanity.

Lately I’ve been… hmh. Rediscovering my fannish side, I suppose. Fallout 4 is coming out in 17 days (and 14 hours and 7 minutes and yes I think it is perfectly normal to have a countdown timer on my phone), and Hallowe’en is coming up sooner, and there is a local convention that has specifically mentioned costuming and there is also an okay to wear costumes at work.

Also the light of my life got me a PIP-Boy. So there’s that.

I am not a good costume-maker, for the record–my interest only tends to spike far-too-close to an event for me to comfortably have time to assemble something–but I am mucking about a bit with assorted paints applied to existing objects. What I am hoping for will be a very low-grade costume, no more remarkable than a sports jacket, but I hope it will be fun.

The Gentleman, after and before.

He made it all the way to 1997 New York, but he’s a little rougher than he used to be.

Still collecting fingers, though.

(Those’ll be shots from Escape From New York and Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell, respectively.)

Twenty minutes into the Future…

During the entirely too excessive amount of time I spent on planes yesterday, one of them offered Mad Max[1] as an in-flight movie. And I saw the summary and grumbled, because the summary ran

In a post apocalyptic world, Australian policeman Max seeks to avenge the death of his family at the hands of bestial marauding bikers. (115 min)

Mad Max, I maintain, is not a post-apocalyptic movie (and dammit, you hyphenate that when it’s an adjective). I would listen to arguments that it’s a world in the slow beginnings of an apocalypse as society crumbles into a new dark age[2], but it ain’t post-apocalyptic. There wasn’t an apocalypse.

I do think it’s part of a really identifiable sub-genre of dark dystopias that are very low science fiction (if any) and that I think tend to get lumped into SF because they’re set “technically in the future” rather than because they’re movies about the effects of a new technology. I mean, things are in the future and it’s different and bad–that’s part of what SF is, right?

(We shall now pause for a regularly scheduled observation that if all SF was was complaints about how everything was going to hell, it would not deserve its title as “the literature of ideas”. Future rants about the reactionary nature of time travel may follow.)

But these movies… you know the kind I mean, right? The setting of Mad Max is undermaintained and there’s been a decay of the social order for some unspecified reason, but that’s it. Escape from New York came out in ’81, and there really isn’t any new technology in there; a bunch of it was probably developed during World War III, but that never really comes up. Dead End Drive-In is a low-tech (and very low-budget) excuse to pen a bunch of unemployed hooligans up in a isolated parking lot and leave them there.

I’m not saying these different-society-plausible-technology movies are bad. Some of them are bad. Some of them are fun. Some of them are pretty cool.

But I really don’t think they’re speculative fiction, and I wish I had a name for the sub-genre. I suppose they’re dystopias, or possibly just near-future dystopias, but I kind of wonder if someone else has already thought about this and come up with a better name.

(NB: Not saying the subgenre of “twenty minutes from now, it’ll be the grim dark future” is exclusively low or no SF–you can look at Rollerball, Death Race 2000, or RoboCop for counterexamples. Or Max Headroom, which is the source of the post’s title. And I have a bit to say about both Max Headroom and RoboCop, but it’s actually still 10 p.m. on my body clock and I think I need a nap, never mind all this sunshine.)

—

[1] Not Road Warrior, not Beyond Thunderdome, not Fury Road, just Mad Max.

[2] The distinction between apocalypse and societal decline is interesting, and one that I suspect largely has to do with framing and speed. (Possibly enhanced by weapons of mass destruction. I suspect that a society that crumbles without anyone having the potential to fire off nukes is going to do so rather more gracefully than a society with said potential, insofar as such processes can be called graceful.)

Oh. Shucks.

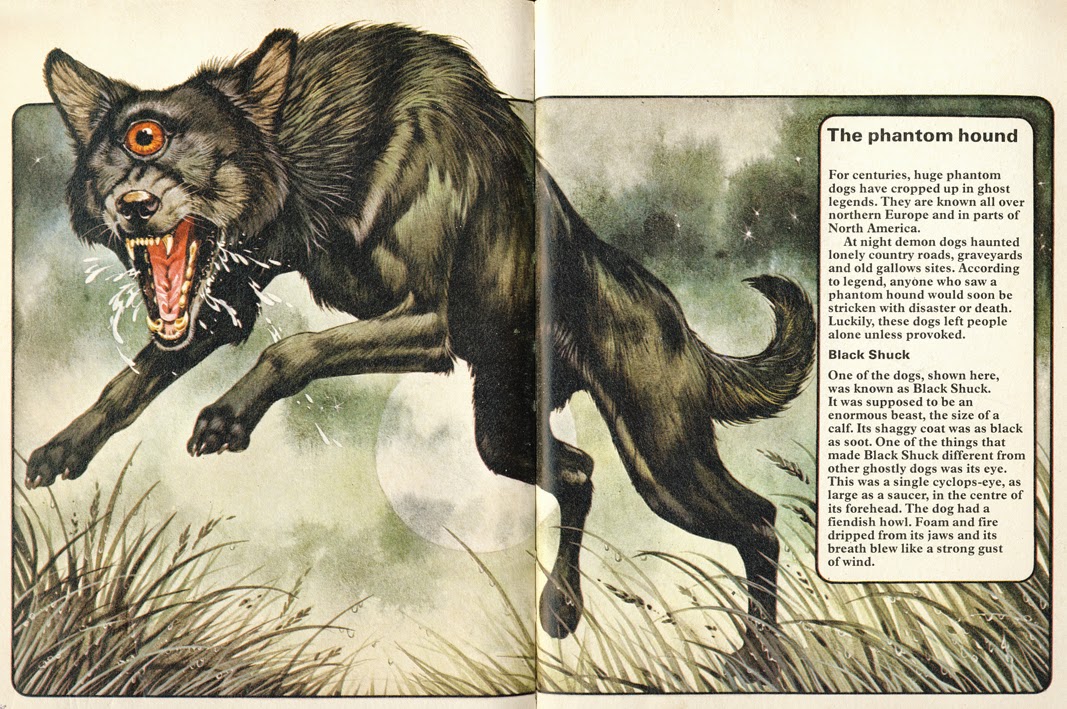

It’s kind of interesting, how many times black canids show up associated with death, and specifically the transition/boundary of death.

Off the top of my head, you’ve got Anubis who embalmed the dead and guided souls to the afterlife. You’ve also got Cerberus, guarding the gates of the land of the dead.[1] But my favourite image in this regard–where my brain goes quickest, and what makes me smile–is Black Shuck. Black Shuck is an East Anglian creature of folklore; he’s a harbinger of death, and seeing him means you’re probably going to die soon.

Surprisingly enough, despite the less-than-friendly demeanour depicted in the image above, the stories mostly don’t seem to mean “soon” as in “as soon as he chews your leg off”. More of a “as soon as you have time for the full horror to sink in and to tell a few people” thing.

(That picture, by the way, is one I ran across around age six. I think I promptly adopted Black Shuck as the most awesome imaginary friend ever. You can do that kind of thing, when you’re six.)

To tangent briefly: the term Black Dog to refer to depression–as in the Black Dog Institute, or the “I had a black dog” animated video–was drawn from Churchill’s references to his bad moods as “a black dog on my back” (something akin to “getting up on the wrong side of the bed”), a colloquialism that also refers back to the black dogs of folklore.

I suspect black dogs have mostly been on my mind, however, because I recently reread Bob Leman’s “Loob“–in which the Goster County dogs are not friendly, not approachable, but ultimately a signifier that things may return to an idealised order, and are described as follows:

…almost a distinct breed, huge rangy dogs with blunt muzzles and smooth black pelts, who stood baleful guard over the farms of the county and patrolled the streets of the town with a forbidding, proprietary air.

It kinda fits.

—

[1] As to Norse mythology: I’m honestly not sure if Fenrir fits this mould or not. Canid, yes; associated with death, yes if you count the end of the world as a death; black, I really could not tell you. Garmr is a blood-stained watchdog that guards the gates of Hel, but again: could be lilac for all I know.[2]

[2] Probably isn’t lilac.